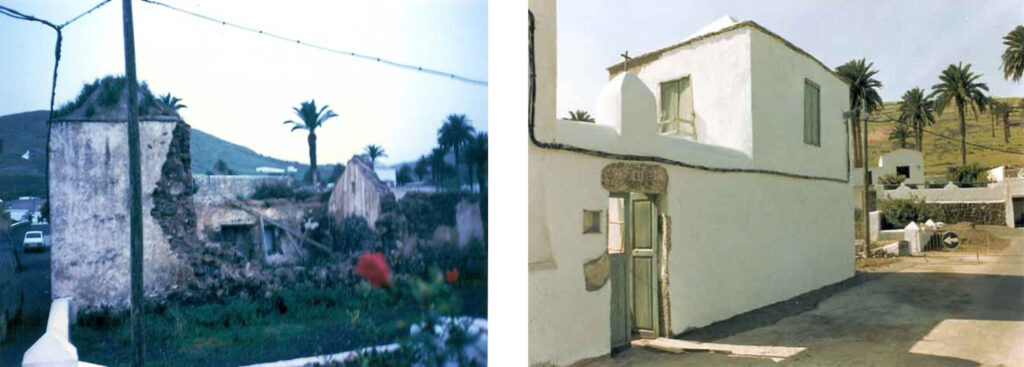

Between 1973-1984 I spent a wonderful decade in rural Kenya where I started my career as a teacher and developed a lifelong passion for planting trees. My experience of teaching with limited books and equipment made a local international school on Lanzarote keen to recruit me because mismanagement had led it to near bankruptcy. I was told that spending my modest savings on a property here would be a brilliant investment, but the tourist resorts here have little appeal for me and I was intending to reject the job offer until I saw the remains of Haria’s old village fish shop. I purchased the property in the late 1980’s with only the street-facing part of the building largely intact (only the walls remained of the rest of the building). I restored the large central room, formerly the village fish store, which is now my living room and whose high roof protects me from summer heat as it once did Haria’s fish supply. I paid 3 million Pesetas (about 15,000 Euros) for the property, and repairs – mainly replacing the living room roof – doubled that cost. Various other extensions have been added over the years. At the time, when I asked the Council for permission, I was told “you don’t need permission to build behind your house”. However, different personnel in the same office now tell me that I really should have insisted on that formal approval!

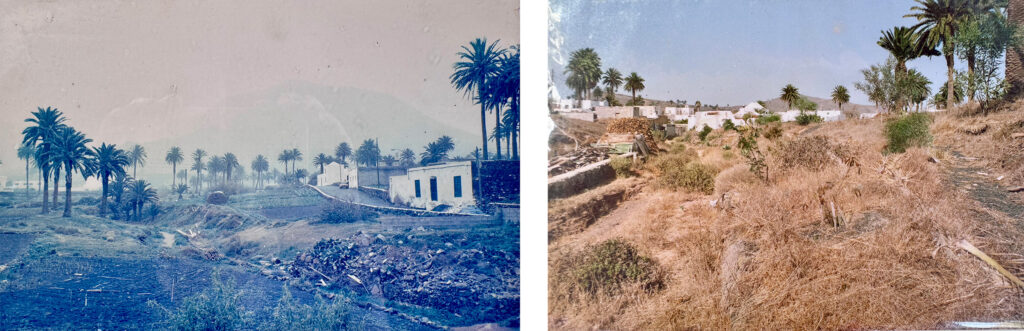

The garden was completely bare apart from four ancient palms, and appeared unsuitable for either building or normal cultivation. But my eyes had been trained by living in arid regions of Africa and focussed on the barranco (a gully formed by water erosion) running alongside the long thin property. In Africa such spaces are highly valued as there will always be ground water available for trees and deep rooted plants. Why such spaces are not valued on this tiny desert island took some time to understand; the only non-fruit tree local people accept is the magnificent Canarian palm, but not for its beauty but rather its drought resistance, growing even in years with zero rainfall. Feeding the palm fronds to goats produced milk and meat, ensuring survival despite drought, a practice that existed before Spanish colonisation, and is still sometimes practiced. However, the general mindset appears to be: if you grow trees, you don’t grow potatoes, and you starve. The palm’s use as goat fodder made these trees tolerated in fields, as agroforestry systems known as palmerals, and proof of this were the four palms I encountered in the garden when I arrived; the only thing that was growing.

In the first photo, the view is to the west where you can see the four palms (on the left) and the barranco snaking to the right.

The second photo is the view east towards the house, with the four palms in the far right corner.

When I started planting trees my neighbours laughed at me saying ‘trees don’t grow here’. As this was increasingly proved wrong, amusement sometimes turned to anger, some of my trees were sprayed with herbicide and killed. A new generation has different attitudes and antipathy is increasingly replaced by interest. My first plantings were undertaken as part of Garden Organic’s ‘drought defeater’ project involving non-native species. Various influences, especially Dr. Bramwell’s study of Canarian flora has persuaded me that local species are best and the only trees remaining from that project are some species of propolis, native to the Atacama desert in Chile, where they survive in rainless regions aided by moist air common in this village.

A variety of birds were attracted as the trees grew, the Sardinian warbler and our local sub-species of Blue-tit quickly became resident, hoopoes and shrikes are common along with species my eyes are not keen enough to identify, but expert friends regularly spot species that the books say are not native (such as the Canary itself). A couple of water features have reinforced this attraction. As the trees grew, they modified conditions for other local flora, both introduced and self-seeded, which have filled available space. Local lizards and insects were attracted to the garden, and Canarian tree frogs (not native to this island) have been introduced to the pond. My experience of re-wilding has been similar to others I have read of, whereby establishing native flora soon attracts local fauna. The more things develop, the less work there is to do. I have observed that there is always something in flower, even in the hottest, driest months, therefore it is clear that our plants have evolved to share out the services of pollinating insects, providing nectar throughout the year. For example, our two species of Aeonium, my textbook says that they both flower in May/June, however in this garden they reliably take it in turns; first the rare yellow flowered balsamiferum, then the common pink flowered lancerottense – a lovely display!

The unique stone mulch cultivation system developed here permits cultivation in desert conditions and was widely adopted wherever available. Before road construction in the 1960’s enabled the transportation of lapilli (lightweight volcanic ash, known here as ‘picon’), its use was limited to places where there was easy access. A layer exists a meter or two below the clay soil of this garden, the barranco that runs alongside the garden gave access to that lapilli strata and its transfer to the surface caused the ground above to collapse, the far section of the garden consists of two distinct levels – a problem for construction or farming but it has usefully formed contrasting zones appreciated by plants with different needs.

At first I tried to combine my tree planting plan with an investigation of picon mulch and its potential use in forestry. I planted 20 leucaena seedlings so each had alternately a layer of picon or not. Although the seedlings with the protective mulch were the only ones to survive the summer heat, the deficiency of my experimental technique was quickly exposed by Professor Hall at Bangor university, as he explained, I should have used randomised selection to decide which seedlings had the ‘picon’ treatment if I wanted my experiment to be taken seriously.

I was enrolled in a ‘drought defeaters’ project by the group known as ‘Garden Organic’ to investigate tree species that could survive desert conditions. I thought the project was badly organised and the only trees that remain are some species of prosopis, native to the Atacama desert of Chile where they can survive years without rain by extracting water from the foggy air common there. The benefit of humid or misty air to cultivation was often confirmed by local farmers I interviewed – although as I explain elsewhere (stone mulch page), the connection between picon use and this atmospheric moisture has been widely misunderstood.

Although my intended subject for my MSc thesis was rejected because of my non-random planting method, another target of investigation emerged; the Canadian cloud physicist Dr. Robert Schmenauer had recently pioneered the use of cloud-catching nets on the cliff tops above a Chilean village which intercepted enough water to supply the village. I had noticed how the only surviving specimens of Canarian Pine (from a past forestation project) were those who were intercepting clouds on the hillsides. I contacted Dr. Schemenauer who helped me prepare the project I gave to the then mayor of Haria Council. This was the first published proposal for the use of cloud catching nets to kick-start reforestation and the restoration of the cloud-forest that once was a feature of mount Aganada (cloud-catching page).

While researching at Bangor university I became increasingly persuaded of the importance of protecting native species from foreign invaders. The studies of Professor Bramwell have made clear that the Canary islands have a huge botanical wealth that is increasingly endangered in this way. A region of Gran Canaria for example is called the ‘dragonal’ – but every one of the magnificent eponymous drago trees has been replaced by eucalyptus.

For the last four decades then, the theme of the garden has been to encourage and protect native trees and other local flora.

My admiration for the ingenuity and resilience of the island’s people in surviving such harsh conditions is immense. However the mind set which such survival requires has little time for activities such as mine. This was soon made clear by a neighbour on the other side of the barranco who sprayed herbicide to kill some tamarix trees I had planted. In the past, if you had a tree in your garden it would take water needed by food crops, greatly increasing the risk of starvation, so, with the exception of fruit trees and the palms whose fronds fed goats, trees are unwelcome here. Before roads and transportation made lapilli supplies widely available the ‘gavia’ or ‘bebia’ system (still seen in neighbouring Fuerteventura) was used – anywhere where run-off created a puddle that persisted for 2 or 3 days was judged to have enough ground moisture for a crop, but those same conditions favoured unwanted plants so a back-breaking amount of weeding is essential. This might explain how the local dislike of trees extends to much of the rest of our native flora. Things are changing however and one metric of this is the increasing rate of uptake of the surplus red-list protected plants I leave with at neighbour’s farmers supply store who gives them free of charge to customers..