2016: A Very Earthly Matter of Clouds (published article in Diario de Lanzarote) written by Saúl García. English translation of text below image.

A very earthly matter of clouds

David Riebold began a project more than ten years ago to harness cloud water and reforest the north of the island. The project was carried out, but without his input, and it was a resounding failure. No trees have grown in Montaña Aganada.

David Riebold built his house in Haría using what little remained of an old fish market. In the back, he created a garden with native plants and trees that demonstrates that vegetation can also flourish in Lanzarote. Riebold is a science teacher at a school in Las Palmas and has lived in the house for many years, returning to it on weekends. He holds a Master’s degree in forestry and agroforestry from the University of North Wales, and in 1993, he included in his thesis a study on the traditional use of unusual water sources in Lanzarote for cultivation and forestry and their future potential. That work already mentioned the possibility of installing mist collectors on El Risco to extract water from the clouds and repopulate the area. This was not a world first, as this experiment had already been carried out in the Atacama Desert, but with the aim of obtaining drinking water. There had also been some experience in the Canary Islands.

Riebold contacted Professor Schemenauer, a pioneer in this type of project, and also cited Laguna professor Victoria Marzol, “whose advice and guidance will be required if this project is approved,” he noted. The water that could be obtained in Lanzarote would not be for drinking, but for reforestation with native species. Reforestation would bring about the recovery of the natural life associated with the forest cover and would serve to prevent soil erosion, promote ecotourism, and attempt to restore the aquifers in Haría and the efficient use of water. The benefits seem unquestionable. In the past, there was a small forest on the island, as revealed by the deep layers of soil that are still found in the highest parts of Aganada Mountain, next to the small forest, which was the scene of the first reforestation of the island in the 1960s, and of others since, which have not had the desired success. In 2003, Riebold submitted a proposal to the Haría City Council for a mist-catcher project. As he explains on his website, “Shortly after the mayor accepted my proposal, I was offered an irresistible job in the United Kingdom. And —despite staying four months a year in Haría and stipulating as a condition for accepting the job that I have a license to travel and work on the project— this meant that I was completely dependent on the collaborators at Haría City Council to maintain my participation.” In August 2006, New Scientist magazine published a report on the project, quoting Riebold. Starting in 2007, after numerous meetings, the City Council dropped his support, and shortly afterward, a very similar project emerged, led by one of his former interlocutors, Juan Manuel González, who had been vice president of the Youth Coalición Canaria and was on the CC electoral list for the Haría City Council. González is a biologist and, between 2006 and 2010, was project manager for the public company Gesplan. In 2008, he presented the project “Mist Collectors, Phase 1” at the Zaragoza Water Expo, co-financed by the Haría City Council and Lider through the Lanzarote Rural Development Agency. At that presentation, he gave the talk “How a Cloud Can Become Drinking Water,” revealing the production of up to five litres per day on each of the eight screens installed in Haría in 2006*, according to the note sent that year by the Lanzarote Island Council. The current situation of Aganada Mountain and the state of the fog collectors leave no doubt that the project was a resounding failure. No drinking water was obtained, nor has a single tree grown around the fog collectors, most of which are completely broken. According to Riebold, they are placed too high. They should have been placed lower to better collect the fog. The other problem he cites is that the right species were not planted. But there is a major error on the main property. Water pipes run from the fog meters, which, in order to irrigate the trees that were planted, would have to defy the law of gravity, since the property is on a slope and the trees Fog catchers are located at the bottom. “If they had taken the project away from me, but at least it was working, I would be a little less unhappy,” says Riebold, who says one of his frustrations is the amount of time he’s wasted in useless meetings. He asserts that his intention is not economic, because he would give up the project, but rather his goal is to reforest the area by doing the project well, placing the devices correctly, and focusing on species like wild olive and mastic trees. He believes they could grow in a short time, and then the fog meters wouldn’t be necessary because the leaves would collect the mist.

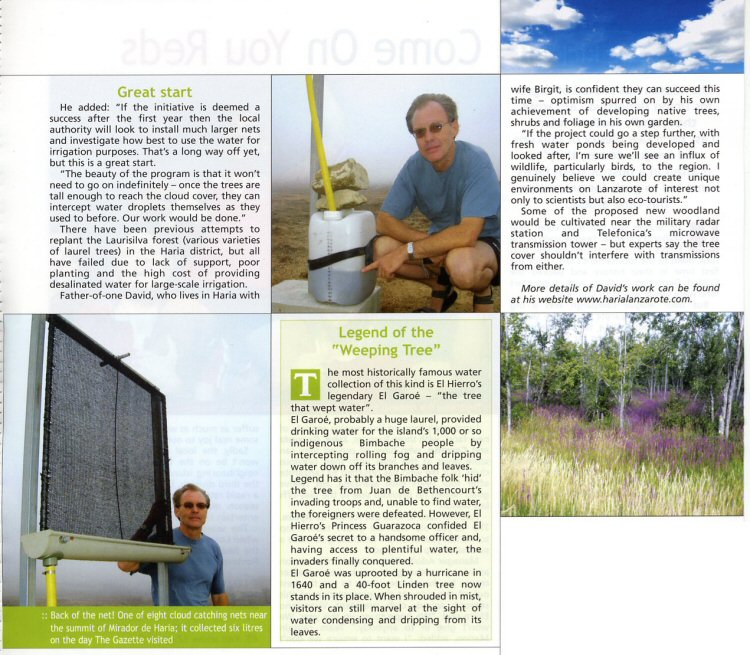

2004: The Cloud Catcher (published article in Lanzarote Gazette)

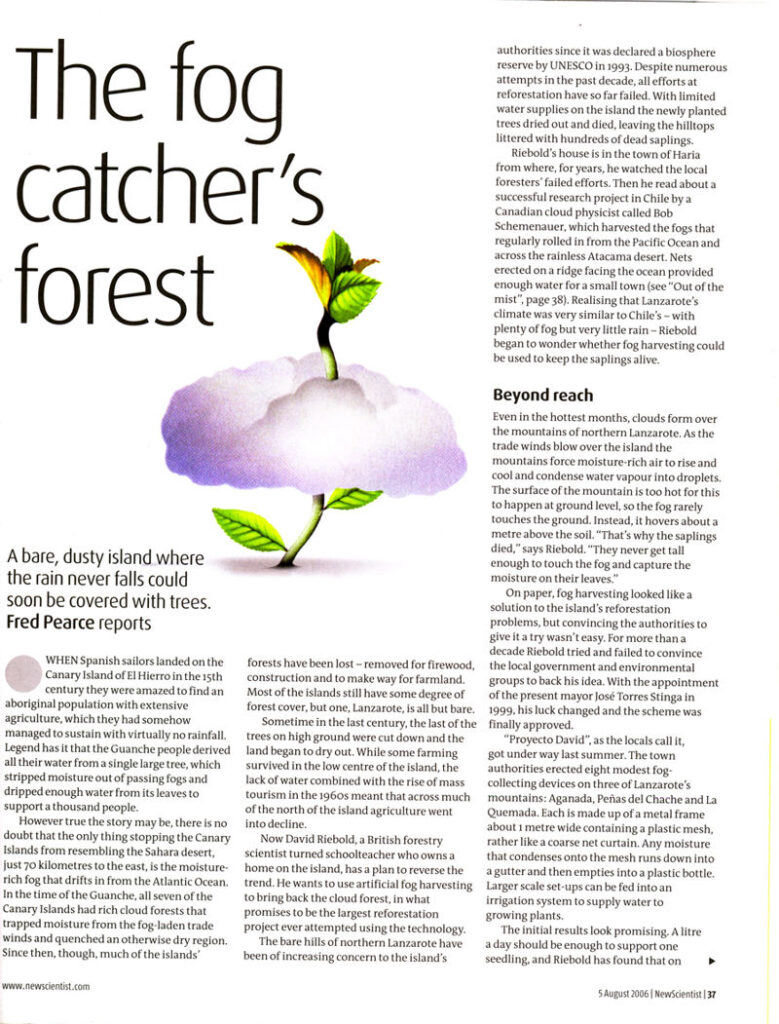

2006: The Fog Catcher’s Forest featured in New Scientist written by Fred Pearce.

2005 (English translation below image):

As part of the environmental policy adopted by the northern municipality, in line with the initiatives proposed in the municipality’s Local Agenda 21, Haría will have mist collectors to collect water. This innovative measure is part of a study conducted by Mr. Riebold, a resident of the municipality who specializes in environmental issues. Riebold presented his proposal to the City Council, where the feasibility and potential use of this system were recognized. A group of environmental educators from the City Council also designed a project with the intention of implementing it. This project is currently co-financed by the Leader+ Community Initiative (61%), which is in turn managed by the Lanzarote Rural Development Association (ADERLAN). nitially, mist-collecting fog meters will be installed at the four stations under study to analyze the amount of water collected per square meter. In a second phase, “fog catchers” will be installed only at stations where a certain volume of water has been collected.

The installation of these devices serves several purposes, such as aiding agricultural supplies, supplying ornamental crops, and restoring and reforesting Aganada Mountain. This environmental measure will also reduce erosion of the mountain, and will regenerate drinking troughs and watering holes.

The Councilor for the Environment, Marciano Acuña Betancor, states that fog catchers are an excellent tool for ecological intervention. Therefore, for their implementation, he is willing to establish appropriate contacts with entities with proven experience in this field, such as the Canary Islands universities, the Ministry of the Environment of the Canary Islands Government, the Technological Institute of the Canary Islands, the Cabildo of El Hierro, the Catholic University of Chile, and the Canadian Consortium for Research on Water, Agriculture, and the Environment, among others, as well as any individuals and companies willing to offer their collaboration in studies on the behavior of fog and its potential use as a hydrological resource appear to have moved beyond the merely experimental phase, as evidenced by the fact that in 1999 there were as many as 48 study sites distributed across 19 countries, with the United States, Chile, and Germany accounting for the most experiments. A number of projects aimed at supplying drinking water are also underway in Chile, Nepal, Oman, Spain (Canary Islands), Cape Verde, Namibia, South Africa, etc., with interest also shown by China, the Philippines, and Kenya.